It’s night, and the frogs are calling.

Being out in the falling darkness is like entering into the mystery. The blues deepen; the shadows gather. The creatures who live in forest and lake, bog and pond, slyly make their presences known.

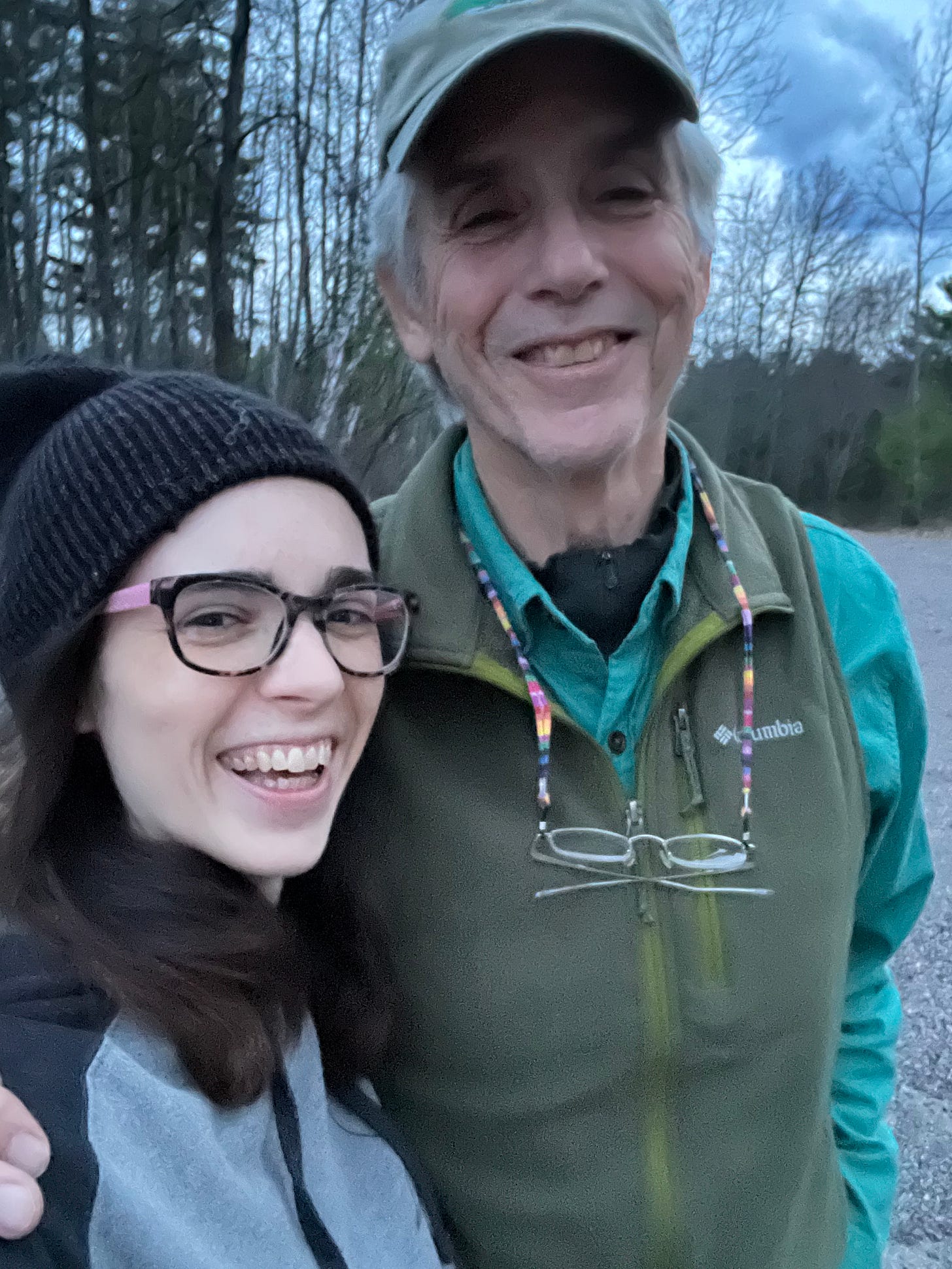

Meanwhile, my dad and I have arrived to conduct a frog and toad survey.

I know, I know…some of you are giggling, while some are nodding. For some, frog and toad surveys are the stuff of ordinary life, and for others, they may sound as close to normal as Frog and Toad Are Friends.

Frog and toad surveys (or as my dad calls them “the frog count”) have been a fixture of my life since I was a small child. My parents would bundle me into the back seat of the car and I would hop out with them at all the stops, cupping my ears to better hear the deafening chorus, slapping at mosquitoes, wandering down to the edge of the lake or bog. It would grow late and I would fall asleep in the back, feeling soft and warm in the darkness with my parents murmuring in the front seat. (“I’d say that’s a 3 for spring peepers.” “Nighthawks!” “Watch out for that deer….”)

As an adult, I don’t do the frog count quite as often. But I still get the same feeling—that contentment mixed with the thrill of being outside in the night, knowing there is so much that’s unknown.

Light lingers on the horizon at our first few stops. Everywhere, the lusty roar of the frogs is deafening. WE ARE ALIVE, the tiny creatures proclaim from wetlands and ephemeral ponds. WE SURVIVED WINTER. LET’S MAKE OUT.

Indeed, the ice only came off the lakes about a week ago, and snow still lingers in some chilly bogs. I, too, feel the relief that spring has finally arrived. Truly, the unfurling leaves, the greening grass, the warm wind—all of it feels like a miracle.

There are spring peepers calling. Wood frogs. If the route encompassed some meadows, my dad informs me, there would be chorus frogs. At one place, the gaseous bellow of a leopard frog underlies the relentless roar of the spring peepers. And at another, toads trill.

The darkness deepens. The lakes we stop at turn into deep mysteries. Splashes carry across the black waters. Loons make panicked cries, then slowly seep into silence. A barred owl utters baritone hoots somewhere in the shadows of the trees. Its smaller relative, the saw-whet owl, can’t stop beep beep beep beep beeping, the sound so monotonous my ears discard it until my dad points it out to me.

We make more stops, getting out of the car to cup our ears and listen. There is a scent like tobacco used in some Indigenous ceremonies, though we are out on a back road against the edge of a vast wetland, and tobacco does not grow here.

On the next road, a whip-por-will is calling in the cutover. Whip-por-WILL! Whip-por-WILL! WHIP-POR-WILLLLLLL!!!!

We drive further. Woodcocks say their nasal peents in the darkness. PEENT. PEENT.

I hear about a dozen, though Dad only catches one. I reflect that if you didn’t know where these noises came from, you would think that you had arrived in a magical world. These sounds are extraordinary. Wild. Otherworldly. Yet they belong to our very ordinary world, if we trouble to walk outside, into the night.

The darker it gets, the more I feel as if I’m softening into my own bones. The urge to drift away into dreaming is almost irresistible. Instead I make a list of charismatic species I would like to see flickering through the darkness: “Wolf, fox, lynx, bobcat….”

“What about a moose?” Dad says.

“A moose would do.”

We don’t see any of them, but we do see a fat brown porcupine scuttling across the road. We see lots of white-tailed deer.

And isn’t that enough? We might wander the world looking for some change we are craving, some insight, some awakening, but the nighttime is a portal if we allow it to be. Entering into the darkness—willingly, eagerly—is a crossing of a liminal space. We are entering a world that we are protected from, with our electric lights and our insulated houses. But it’s also a world that we belong to. The nighttime is a part of us, and I believe that a part of us craves it. Our bones hold some ancient memory of standing beside a fire, outside in the wild night.

“How long have you been doing the frog count?” I ask Dad.

“Oh….” He rummages around in his memory. “Thirty years?”

Long enough to make it a ritual; every stop, a familiar greeting.

On some empty county highway, surrounded by wetlands teeming with spring peepers, another car approaches. I turn on the flashers and the car stops on our other side. They’re worried. Are we okay?

“We’re good,” my dad says. “We’re just listening to some frogs.”

I did frog counting for about 4 years and it is indeed magical. When we moved in 2020 no routes were available in the new area but we still do identify the calls and rate them 1, 2, and 3. I am so grateful for the learning expereince and now the remainimg frog populatios.